Blog

Norman Dott

8th November 2017

One of the quiet heroes of Edinburgh healthcare.This year I’m working with the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the Western General Hospital, to explore its practice and mark its transition to a new building at Little France. There are three Creative Fellows involved in this section of the programme. Susana Cámara Leret is the Design Fellow, Alex Menzies and Florence To are collaborating on the Music Fellowship, and I’m Language and Cognition Fellow.

As part of the Art and Therapeutic Design programme, this is not simply a writing job. My experiences so far have inspired several new short fiction pieces, which you may have heard at Flint and Pitch or EIBF Unbound this year. I have also been looking for a way to contribute to patient recovery, and such an opportunity has arisen for the remainder of the fellowship. More on this later.

One rich area has been the history of neuroscience in Edinburgh, which I unearthed through the case notes of Norman Dott. He was a compelling figure in many ways. After a motorcycle accident on Lothian Road sent him to hospital, Dott became so interested in the process of diagnosis and the patients around him that he turned to a career in surgery, where his mechanical skills were to find their place designing tools for the emerging field of neurosurgery. Before the Western General was constructed, Dott operated in Ward 20 of the old Royal Infirmary, directly under the clock tower you can still see from Lauriston Place.

With the writer’s eye, I notice the details that assemble his character: strict with his junior staff, but gentle and candid with his patients; regularly dealing with life-changing traffic accidents, but never losing his enthusiasm for a powerful car. His operations could take eight hours of exhausting attention, yet he always made his evening rounds of the ward; and first priority on Christmas Day was to take his family to the hospital to entertain the patients.

Reading the case notes is a fascinating and emotional experience. Dott describes each patient’s background, not just the signs and symptoms they present. The reader gets the sense of the character of the patient; gets to know them a little. Even without medical training, I can often follow Dott’s reasoning to a diagnosis, and the course of the subsequent operation. He logs the patient’s condition when safely returned to the ward, and it hits very hard when you flip the page to find an image covered in thin white paper — because these images are post-mortem photographs of that patient’s brain.

Dott maintained correspondence with many people whose lives he saved, years, even decades after they were discharged. Certainly there was an element of courtesy to these letters, but we can also see him working to build the emerging field of neuroscience — and it becomes clear he has retained the case notes of unsuccessful operations because there is something to learn from each.

I was pleased to discover that reading aloud was a feature of his upbringing, with a local link to a particular favourite, Robert Louis Stevenson. I cycled out to Spylawbank Road to get a sense of Dott’s beginnings. Here Norman constructed his 10-seater sledge, and would not send it plunging down the twisty corners of the icy Kirk Brae until every seat was occupied by a local child. It’s strange to see, in that childhood recklessness, the beginnings of the life path which would create a pioneering surgeon.

Audio Jam

27th October 2016

Time loops and tempo changes.If you’ve caught any of my gigs in the last few years, you probably heard some stories with a soundtrack. I got fed up at the mysterious power musicians had to work the emotions and decided to use it for my own ends. I find composition a harder creative process than writing, however, and difficult to make enough time for.

So I signed up to a weekend audio jam with the action-packed Edinburgh Game Symposium. In a game jam of this type, you try to produce something rough but interesting to a theme, within a tight timeframe. They teamed me up with Sarah, an audio engineer specialising in spoken word; Maeve, an audio engineer specialising in mixing and sound design; and Aurelie, a composer and DJ. We happened to all be users of Ableton Live.

The weekend took place in the Roxy, a beautiful repurposed church where I once sat a maths exam. Friday night was supposed to be for relaxing and socialising, but we ignored that and got right into it, clustering around one half of a folding table. The theme was “time travel”. Here’s our initial list of ideas:

- Tell a story backwards.

- An audio diary of past/present/future.

- Randomised snippets of music using Follow Actions.

- A story told by an old guy to his younger self.

- Describing an incident from the past/present.

- “Fuck about with tempo.”

- Crossfade period-appropriate instruments as a journey through time.

- Story of a plugin that breaks time; the temporal ‘prime directive’.

- Madness expressed through chaos and order.

- The “Unsound” applied to time travel.

- Palindromic music with reversed instruments, perhaps in a round.

Towards the end you can totally see the influence of Star Trek: Voyager and The Black Tapes Podcast. I had been at an IGDA Scotland event about game jams where I heard wise advice to throw away your first three ideas, because they’re too obvious. I’m glad we did this. We settled on a soundscape-audio-drama-thing telling the story of a particular incident from viewpoints before and after it happened. We never actually explained what that incident was: a disruption of time caused by reckless experiments. Similar stories have been done before, but it sounded fun and just complicated enough for a jam weekend. Also, I had a labcoat left over from a Halloween zombie walk. So we went home on Friday with our project already blocked out, and that turned out to be a very good thing.

A less obvious benefit of this project was an easy division of labour. There were two characters, and each had their own theme. Maeve and I would write a character each; Aurelie and Sarah would write a theme each. It was only when I was alone in the theatre upstairs, fighting grumpy wifi to read about the Einstein-Rosen bridge, that I realised I had come to a music jam and agreed to do the bit that was the same as my day job. But hey.

So Saturday featured writing, sharing for feedback, and a nice lunch. We situated the lab in Grangemouth, for which I blame Maeve. By 4pm we were ready to go into a hot studio to lay down the vocal parts. We recruited organisers Luci and Sam to do news bulletins; Aurelie supplied some French radio chatter; and the rest of the team went to polish things up overnight while I sloped off to see John Carpenter live at the Usher Hall.

I feel like you don’t really experience a true jam/hack event unless you have a disaster and have a panicked rush to finish everything. I was still humming Assault on Precinct 13 when I got in about 10.30am on Sunday and learned all our audio from Saturday had flatlined. Which meant the producers hadn’t been able to work overnight. Uh-oh.

So we rushed back into the studio, and did it all over again, getting in the way of other groups who desperately needed to record. We had time for about twelve minutes worth of hasty rehearsal during the “Well done! This is your time to relax!” break, before we were thrown on stage to perform The Grangemouth Incident live.

And y’know what? It went fine.

I’ve collaborated with quite a few groups of people before. Some have been great and some have been rocky. I attribute the success of this weekend to a clean breakdown of effort — so nobody became a stressed-out bottleneck — and everybody leaving their ego at home.

Thanks to Luci and everybody else who made the weekend fun. Same time next year?

A Week With Coney

29th July 2015

A mysterious coffee shop and a swollen ankle.Sunday

I survey a location in central London, receiving messages by text and phone from a man I have never met. I briefly consider entering an unmarked building to occupy a vantage point in their lobby. Shortly thereafter I learn what that building actually is, and realise that would have been a very bad idea. As Wimbledon plays behind us on a giant outdoor screen, I notice a stranger I think may be on our team. Making eye contact, I blink, slowly, to acknowledge her. Startled, she looks away.

We gather on the stairs of a landmark you know. The target shows, anxious and clutching a briefcase. We fan out around him, trying to look like tourists. He makes a sudden U-turn. Has he spotted the tail or is he having second thoughts? I pull the old parallel street trick and come at him from another direction. He enters a public building. A couple of the team slip ahead of me and one guy runs a ham-fisted, clumsy distract. The move is made. Our target phones the police.

I meet K for a late curry and a staggeringly expensive taxi to the Waterloo train. Her neighbour has a flagpole. On it, the Union Jack hangs limp.

Monday

An early start in Surrey. We drive past a huge, empty racecourse to board an early train. Both eastbound and westbound tracks terminate at the same destination.

At offices previously occupied by a national newspaper, in a room with two head-shaped holes in the plaster wall, I meet a diverse bunch of interesting theatre people. I learn about, then introduce M, a director who inserts chunks of Shakespeare into the drops in trance music.

We hear about an early Coney project, A Small Town Anywhere, and explore the idea of an audience experience which begins when they first hear about the show, and only ends when they cease to think about it. Our game design process devises a new version of Grandma’s Footsteps where there are two Grandmas and they both rotate.

Tuesday

Today the workshop will spill out onto the London streets. During the warmup I get knocked over and feel my foot twist as my body goes down. Within three minutes my ankle swells up. It looks like somebody has inserted a golf ball beneath the skin.

Bandaged up, limping like a Cold War spook, I practise tailing in the street with A. I notice an old organ manufacturer, a building named 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10, and a caravan left over from Temple Studios. I lose her briefly while adjusting my boot. Reacquiring her down another street, I blend with a crowd of lunchtime smokers and feel like I am playing Assassin’s Creed. We are supposed to return in exactly 23 minutes. We are late.

After lunch we work on a cover story and five of us do covert reconnaissance of a nearby square. We notice a pop-up store which changes weekly, an underground tunnel, and a smokers’ entrance to a private members’ club. B observes someone counting money in a restaurant doorway. Another B spots a man who sits in his car outside an office for ninety minutes without moving. By purchasing a muffin and showing interest in the vendor’s music, H learns where to buy drugs.

At night I ask a passer-by for directions to the Bishop’s Finger pub. He asks if that is something to do with bikes.

Wednesday

The day begins with tall tales and then an organised game about lying. I am disappointed when my story of accidentally killing a tank full of frogs for a school project does not convince. A, however, successfully conceals the true version. We discuss audience handling and how best to create a manifesto.

We also consider how to give a surprise gift, and the unexpected positive ripples it can create in somebody’s life. It is a subtle art. Personal is good … but too personal is creepy. Magical is good … but too magical is freaky. And valuable is good too … but too valuable, and there is an implied obligation to reciprocate. Perhaps the gift itself is the knowledge that somebody out there cares enough to give you a gift.

Using train, foot and tube, I rush over to North Greenwich to meet F&F. I lose my bearings in the strange pedestrian space around what was formerly the Millennium Dome. As I approach the venue, a plane above my head carves a slow trail through the rainclouds.

The bus back into town takes an hour. I talk to a trumpeter who assumes I have been at a massive church gathering. When I reach bed and take off my boots, my entire right foot is covered with angry red and purple bruising. It looks like a truck has driven over my toes.

Thursday

Some of the group have left, but the remaining members will devise a scratch performance piece today to be delivered on Friday. There is a definite conflict between the real excitement of this project and the general lack of energy in the room after three busy days.

We riff on the division between tea and coffee drinkers and some ideas emerge. Our notes include the words WINDOW OF CONTROL, PAYSLIP HISTORY and THE HIDDEN REFLECTION. Another reconnaissance, which feels very psychogeographical, locates interesting buildings, a usable phonebox, and a local juice seller who charges tourists for directions. I order a rare afternoon gin and tonic to get an extended look at the pub.

The part of me that directs shows becomes anxious at the lack of tangible progress by day’s end. I try to ease off and have faith in the process and the creative people around me.

I hit my old stomping ground of London Bridge to meet B. In an alley down the side of a pub, we relax and talk about writing, cats, zombies and poker. After she leaves, I head to a certain establishment on Middlesex Street one hour before closing time. A man at the door tells me it has closed an hour early.

Friday

At breakfast I see a woman who eats only fruit. She has four large plates which do not fit on her tray. One is stacked with watermelon. One is stacked with melon. One is stacked with pineapple. The fourth has a selection of other fruits. The total volume of fruit is slightly greater than the volume of her head. She eats it all.

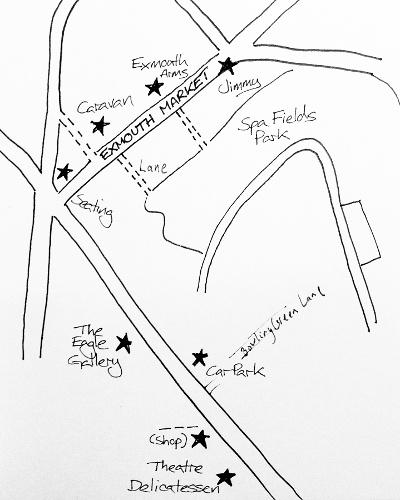

Rain batters London as we plan what has become The Curious History of Mr Fleet. T is loading up a platform which will deliver audio and text messages to our players. M has brought a massive treasure chest of tea. We scrabble to generate maps, stories, little presents and unexpected experiences. There is talk of another reconnaissance to build an alternative, indoors version. We opt to tough it out and commit to the outdoors version. There is a ukulele rehearsal which seems to last hours.

I leave at 4.15pm to secure a table in the Exmouth Arms before the Friday evening rush. I flit from canopy to canopy through the pouring rain, a bit worried that nobody will turn up. In the pub, I drink a beer called Dark Age, read a Frederick Forsyth novel and leave a pack of cards visible on the table. When, an hour later, the audience arrive in small groups, I tell them about Mr Fleet’s coffee shop and his gentle powers of intuition. Then they read my mind.

The working week concludes in the park, on the site of the largest tea house in London, with vocal stylings from a three-girl ukulele combo and a surprise appearance by a tap dancer. It is a soggy, but strange and beautiful thing.

At drinks afterwards, I feel both elated and sad, buzzing with what we created and pained that we don’t get to do it again next week. People drift off, until the final scramble for the last tube. M and I catch it with seconds to spare, spilling tea and umbrellas.

I realise as the train slows that I didn’t get to say goodbye to H. But she appears out of nowhere, through the barriers at my stop. I wait with her until the night bus comes, then limp in the direction of a late night sandwich.

Saturday

The fruit lady repeats her breakfast performance. I check out and wander the streets with my case, lingering over coffee, comics and coloured markers.

In the window of Pollock’s Museum and toy shop, faded and bent, I see a miniature cardboard theatre I remember from my childhood. Written on the front of the stage is an enigmatic message I never understood. Out of curiosity, I search the web for it. No hits.

Hana Feels

30th April 2015

Learning to talk about self-harm with an interactive web story.So I’ve been writing too many zombies lately. Neighbourhood Necromancer and Zombies, Run! both have a lot of zombies in them. (Eagle-eyed readers may spot a clue in the names.) I was just feeling that I needed to do something more mainstream, when the Hana Feels project showed up.

This is an interactive, web fiction about … well, if you haven’t already, maybe you’d like to try it without spoilers? Read Hana Feels. I’ll use the terrific art of Scribble Imp as an eye break:

![[Hana and friends]](/images/blog/300415a.jpg)

Hana Feels is a story about mental health; specifically, self-harm. It had been in “development hell” for a while and I was brought in to restart the project and complete it by the start of April 2015. Previous commitments meant I couldn’t start until January.

I don’t mind admitting it was an intimidating prospect. The timescale was tight: three months to come up with a good concept, learn new tech, write 25000 words, code and style it all, and do the game-like balancing that would be required. All that stuff can be solved with time spent at the keyboard (and some colourful language directed at CSS’s quirks) but the more intimidating challenge was to represent self-harmers in an accurate and sensitive way.

The original premise was to tell the story of Hana, a girl who self-harms, but to allow the reader to adjust her feelings up and down. The text would show how this changed Hana’s perception of the world. We have to credit Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest for inspiration here. However I didn’t fancy repeating Zoe’s work, and wondered if I could find a different approach which might still be appropriate to the subject matter.

There has to be a reason to put interactivity into a story. In this case, I thought about how awkward people feel when they have conversations outside their comfort zone. And talking to a friend or family member about their self-harm certainly falls outside the comfort zone for most people.

So I decided on a conversational approach. Instead of inhabiting Hana’s head, we observe the conversations she has with the important people in her life: a helpline guy, her boss, her best friend and an old dude who comes along later. At the end of each page, we get to choose what that person says to Hana, and at the end of each session we peek into her journal and see how it made her feel. It’s not possible, or realistic, to “fix” Hana in the limited time we spend with her. All we can do is try to help her feel valued, understood and supported. And if she feels better, we can hope for a more positive ending.

Writing this required a ton of research and a certain amount of courage. The timescale was a lot shorter than I would have liked, and in the end I took an additional couple of weeks to refine Hana’s responses; to playtest, if you like. But when some of my test readers commented they felt guilty for saying things they knew would increase Hana’s stress levels, I knew I was onto something.

I chose Twine 2.0 as the tech platform. It’s a popular foundation for personal work and I thought its community would be interested in the project. I spent a lot of time messing with its structure and styles, but even out of the box, Twine is very accessible to anybody who wants to make their own game.

At the heart of the work are two objectives. Readers may know somebody who self-harms, but feel awkward about communicating with them. I hope that by having a dialogue with a fictional self-harmer first, those people will gain confidence and feel informed enough to have a real conversation on the subject.

The second objective is to direct that conversation in a positive and sensitive way. It’s natural to enter it full of well-meaning suggestions and think we are being supportive. But we may not understand the situation as well as we think we do. And we should learn to listen first; to really listen.

This work was supported by New Media Scotland’s Alt-w fund, with investment from the Scottish Government.

Alone Against the Flames

5th March 2015

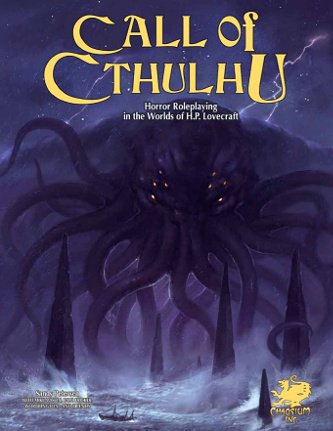

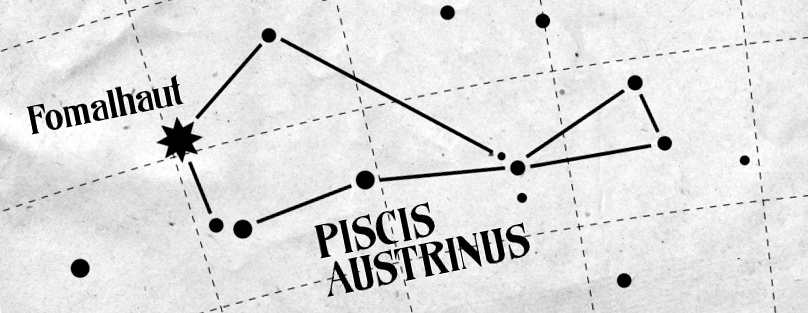

Lessons from video game tutorials applied to tabletop RPGs.During high school, my gateway drug to the literary horrors of New England writer H. P. Lovecraft was the pen-and-paper roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu. Set in the 1920s, it included silhouettes of marauding, tentacled creatures and a map of the world featuring lost cities and occult sites. It was an easy sell.

The attraction of tabletop roleplaying games is that you get a bunch of friends or agreeable nerds together and pit your wits against a problem, or construct a collaborative story. If the referee does their job and the players cooperate, you get atmosphere, excitement, laughter, and a little acting if you enjoy that kind of thing. With the right people it is tremendously good fun, and Call of Cthulhu is no exception.

However, not many of Lovecraft’s stories feature a plucky group of friends getting together to combat cosmic horror. On the whole they concern solitary figures stumbling across cosmic horror and meeting a terrible doom. So it felt natural to play Chaosium’s solo adventures: Glenn Rahman’s chilly Canadian expedition Alone Against the Wendigo and Matthew J. Costello’s globe-spanning doomfest, Alone Against the Dark. They told an interactive story with the “turn to paragraph XX” system. I disappeared into those books for weeks, losing sanity and dying in various ghastly ways. The originals still go for hefty prices on the secondhand market, along with Scott David Aniolowski’s Alone on Halloween and Grimrock Isle.

When I saw Chaosium were doing a major overhaul of Call of Cthulhu, I pitched a new Alone Against book. There is a perception among RPG publishers that solo adventures are a small market, despite the global popularity of Fighting Fantasy and Choose Your Own Adventure books. So I tried to fit a different niche.

Today’s video games have a tutorial which introduces you to the game gradually, as you play. There’s no preparation time; you just pick up the controller and begin. With tabletop RPGs at least one person has to read and absorb the rules before play can begin — and the Call of Cthulhu Seventh Edition rulebook is over four hundred pages. I wrote Alone Against The Flames like a video game tutorial. You sit down with a blank character sheet, some dice and a pencil, and just get reading. You’ll be involved with the story before you even have to define your character, and the references to the free, compact quick-start rulebook are relatively rare.

The story has you taking a long bus ride through the wilds of New Hampshire to your first job — and a new life — in Arkham. If you like Lovecraft or interactive stories, you can download and play it for free: Alone Against the Flames. It’s even hyperlinked to save you all that old-school flicking backwards and forwards through the book. But be careful out there.

I must thank Chaosium editor Mike Mason, for taking a chance on a writer he didn’t know, and my playtesters, particularly Stefan Pearson, who risked his literary reputation by sitting in full view at an international book festival, rolling funny-shaped dice.